Starkloff: A Legacy of Disability Rights

In 1959 at the age of 21, Max Starkloff acquired a spinal cord injury in a car accident. Because the world was not built for Max’s new body and wheelchair, he was forced to leave his friends and family and move to a nursing home where he lived for 12 years. Max was smart and ambitious. As his contemporaries began their careers, started families, and bought homes, Max hungered for a full, meaningful life.

When he learned how to paint, holding the paintbrush with his mouth, Max found an emotional release and the joy of envisioning and creating new possibilities. As he watched the Civil Rights Movement unfold on the nursing home TV, he was inspired to take up the fight for people with disabilities. He had big dreams and connected with others to organize the disability rights movement. Max began planning to escape the bondage of institutional captivity for himself and all people with disabilities.

While in the nursing home, Max got to know the physical therapist, Colleen Kelly. Colleen was excited about his ideas for independent living and joined him in his crusade. Colleen and Max fell in love, married and started a family, leaving the nursing home behind.

Max and Colleen founded Paraquad, one of the world’s largest, most successful Centers for Independent Living. Max’s vision of people with disabilities leading independent, fulfilling lives laid the foundation for the organization. Under their 32 years of leadership, Max and Colleen grew Paraquad into a $4.5 million nonprofit that employed nearly 100 people. Their advocacy led St. Louis to many milestones – including becoming one of the first cities to make public transit more accessible by adding lifts to buses.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Max and Colleen helped lead and shape the disability rights movement. They built Paraquad in the mold of the Center for Independent Living, Ed Robert’s pioneering organization in Berkley, California. The lively activist community in Berkley and growing across the county became close partners, friends, and co-conspirators of the Starkloffs. Spending long days organizing together brought them very close. Colleen and Judy Heumann called each other “sister.” Max and Colleen’s community spanned states and continents as they worked to advance disability inclusion. Days of strategizing would end with dinners that stretched into parties, full of laughter and the connection between people who truly understood and cared for each other. Regular faces around the table included: Yoshiko and Justin Dart, Ed Roberts, Judy Heumann, Charlie Carr, Fred Fay, Lex Frieden, Mike Auberger, Gini Laurie, Marca Bristo, Denise and Neil Jacobson, Tom Olin, Joe Shapiro, Art Humphrey, Bill Sheldon, Jim Tuscher, and so many others.

In 1999 Colleen Starkloff and a citizens’ advocacy group established the Affordable Housing Commission in the City of St. Louis, which oversees a $5M Affordable Housing Trust Fund. She served as Founding Chair of the Commission and worked to ensure all housing created by the Trust Fund include Universal Design features, significantly increasing the supply of accessible housing and making St. Louis a leader in this movement. Colleen organized the first Universal Design Summit in 2002, educating architects, designers, and builders on principles and benefits of Universal Design in homes and communities.

Despite the hard of work of Max, Colleen, and their disability rights movement “family” to get the Americans with Disabilities Act passed, the exclusion and isolation of disabled people persisted.

People with disabilities still struggled to gain economic independence and make meaningful choices about their own lives. The largest barrier? Discriminatory attitudes that kept them either under-employed or out of the workforce altogether. In 2003, Max, Colleen, and their fellow disability advocate, David Newburger, co-founded the Starkloff Disability Institute (SDI) to change that.

Max, Colleen, and David, all professionals with disabilities themselves, built the organization on the foundational tenet of disability rights: nothing about us without us. Disabled people face barriers every day and they are the experts in what support or changes they need to thrive. Every program at SDI was created by and for people with disabilities.

SDI began working with civic leaders to untangle the web of barriers to unemployment for disabled people. The founding trio’s passion and record of success in disability advocacy gained them many partners. In 2005, Colleen developed and introduced a Disability Studies course at Maryville University. Attracting many future disability-related service professionals like occupational and physical therapists, Disability Studies introduced young people to the social model of disability and the community’s vibrant history. This course flipped the traditional script of pity for disabled people, and prepared a generation of students to welcome people with disabilities as their peers.

Max built relationships with corporate partners. When he rolled into boardrooms, with years of experience advocating for disability inclusion and navigating a world not built for him, Max was a living example of a different way to do things. He was a successful adult, with a family and more meetings with world leaders under his belt than some members of Congress, and the founder of well-respected local and national organizations. All he was asking for was people to not write him, and any other disabled people, off as incapable at the first glimpse of his wheelchair. His chair was a tool of independence for the smart, strategic, and innovative person driving it. Employers understanding this reality could change everything.

“I don’t want your pity, and I certainly don’t need it. I’m no tragic figure, and I’m no poster child… I’m just a guy named Max who wants pretty much the same thing you want out of life. I just need a hand with a few things. That’s all.” — Max Starkloff

Working the issue from the other side, SDI developed programs to empower disabled job candidates with the skills and confidence to build careers they love. First known as The Next Big Step, and now the Starkloff Career Academy, this innovative program aimed to level the playing field for disabled professionals in the workplace. Along with cutting-edge career development skills, the founders’ experience in the disability rights movement knew creating community and disability pride were key components to its success. This was not a job placement program. Candidates learned how to be excellent jobseekers and standout in piles of resumes and interviews, empowering them to build their own careers and continue to achieve success throughout their lives. It transformed the future of each graduate.

In 2010, Max Starkloff passed away at age 73 after an illness. Colleen and David Newburger continued working toward their vision of a world that welcomes people with disabilities as they expanded SDI’s programs. Access U and Dream Big were developed to build a deeper foundation of disability pride, self-advocacy skills, and expectations for equal opportunity in disabled youth. Work continued to educate employers and the community about disability inclusion and Universal Design. David Newburger retired from SDI in 2019 to continue his advocacy as the Commissioner on the Disabled for the City of St. Louis. In 2022 Colleen Kelly Starkloff retired, celebrating a 50-year career advancing disability rights, and continues community advocacy and spending time with her and Max’s children and grandchildren.

The Starkloff Disability Institute was Max’s final project, the culmination of a life spent advocating for the full and meaningful participation of disabled people in society. We are honored to carry on his legacy, rooted in the disability rights movement and focused on the most pressing issues our people face: misperceptions about disability and decades of exclusion in professional careers.

SDI proudly recognizes people who, like our founder, have spent their life working for the emancipation, empowerment, independence, and quality of life for all people with disabilities. Max J. Starkloff Lifetime Achievement Award Honorees include:

- Senator Tom Harkin (2014)

- Dr. William H. Danforth (2016)

- Robert H. Graebe (2018)

- Judith Heumann (2020)

- Gina Hilberry, AIA (2023)

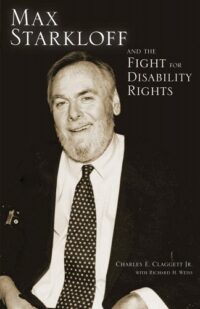

Read more about Max and Colleen in Max Starkloff and the Fight for Disability Rights by Charles Claggett, Jr., and Richard Weiss. Available at Amazon and Bookshop.org. See a glimpse of Max in action in the Emmy-winning 1995 documentary Max and the Magic Pill (YouTube).

Read more about Max and Colleen in Max Starkloff and the Fight for Disability Rights by Charles Claggett, Jr., and Richard Weiss. Available at Amazon and Bookshop.org. See a glimpse of Max in action in the Emmy-winning 1995 documentary Max and the Magic Pill (YouTube).

Max J. Starkloff (September 18, 1937 — December 27, 2010)

- Founded Paraquad, with his wife, Colleen, as a privately funded Independent Living Center (1970)

- Founded the St. Louis Chapter of the National Paraplegia Foundation (1970)

- Secured first ever stateside, barrier-free legislation for local and state curb cuts (1972), acquired disabled parking legislation, labored for access to public buildings and schools

- Established Paraquad as an official Center for Independent Living (CIL) and one of the original 10 to receive federal funding (1979)

- Organized and spearheaded a large coalition of people with disabilities, volunteers and community leaders to support accessible transportation policy

- Lobbied the local transportation authority to adopt a policy that all new buses be wheelchair lift-equipped

- Succeeded when St. Louis was the first city in the nation to have lift-equipped buses on its streets (1977)

- Influenced St. Louis’ new light rail system to endorse and include total accessibility

- Co-founded the National Council on Independent Living (NCIL), served as founding President (1982)

- Served on the board of directors of: World Institute on Disability; Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Missouri; and Gazette International Networking Institute

Appointments/Public Service:

- Research & Training Center on Independent Living and Public Policy – Advisory Committee

- World Institute on Disability, Berkeley, CA; Blue Ribbon Panel, National Project for Telecommunications Policy – Advisor

- World Institute on Disability, Berkeley, CA – Board of Directors

- Leadership St. Louis; Recruitment/Selection Committee

- SSM Rehabilitation Institute – Advisory Board

- American Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC – Committee for National Agenda for Prevention of Disability

- Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. – Research & Training Center Advisory Committee on Secondary Disabilities

- Rehabilitation Services Administration, Washington, DC – National Advisory Panel for evaluation of standards for Independent Living

- Fourth Japan/USA Conference of Persons with Disabilities, 1991, Chairperson of the U.S. Delegation, St. Louis, MO

- Fifth Japan/USA Conference of Persons with Disabilities, 1993, Chairperson of the U.S. Delegation, Kofu City, Japan

- National Council on the Handicapped, Washington, DC. – Official Advisor

- County Commission on Disabilities, St. Louis – Chairperson

- President’s Commission on White House Fellowships by President Clinton – Commissioner

Awards:

- President’s Distinguished Service Award – President George H. W. Bush

- Community Leadership Award – Leadership St. Louis

- Commissioner’s Distinguished Service Award – Rehabilitation Services Administration, Washington, DC

- Mayor’s Arch Award for leadership in disability rights – St. Louis, MO

- Annual Civic Service Award – Maryville University

- Human Rights Award – United Nations Association, St. Louis, MO

- Humanitarian Award – Human Development Corporation, St. Louis, MO

- St. Louis Award

- Sold on St. Louis Award

- Sword of Ignatius Loyola Award – St. Louis University’s highest honor, St. Louis, MO

- Missourian Award – Missouri Hall of Fame

- Doctor of Humane Letters – Webster University, St. Louis, MO

- Doctor of Humane Letters – University of Missouri, St. Louis, MO

- Recognized by National Council on the Handicapped and St. Louis Unit of NASW

- “Max Starkloff Lifetime Achievement Award” established – National Council on Independent Living, Washington, DC

- St. Louis Walk of Fame – Inducted June 20, 2008